How Not To Sell Your Investments

Subscribe to the Mind of a Millionaire Podcast on iTunes, Spotify, or Stitcher.

As we approach another Colorado winter, us Denverites prepare our flannels and snow boots for another chilly winter. It may also be time for various home and auto improvements (i.e., replacing those all-purpose tires or the hot water heater that takes ten minutes to prepare two minutes of a lukewarm shower).

For many investors, our emergency fund can cover certain expenses, like replacing a shoddy water heater or furnace. Others may turn to their investment portfolio to provide cash.

As the adage goes: Cash is king. Though the retreat to cash may seem safe—especially in volatile periods like 2022—it can significantly impact potential long-term returns. Thus, investors should know when not to sell and how not to sell.

If you have questions about investing or want guidance from a professional wealth advisor, call our office at (303) 261-8015 or schedule a free consultation on our website.

THE AVERAGE INVESTOR IS MEDIOCRE

A study by Dalrbar, Inc [1].—a company studying investor behavior—found that from 2000 through 2019, the average stock fund investor earned an annualized market return of 4.25%. The S&P 500 alone returned 6.06% over that same period, so why did the retail investor lag by nearly 2%?

Shoot, investing in a low-cost S&P 500 index fund—one designed just to track the index—would've outperformed the average investor.

It comes down to behavior. When the market falls 20+ percent, our stomach churns, and that "safety" chute into a soft bed of cash seems like the correct move—no more worrying about market volatility.

As the Dalbar, Inc. study illustrated, that may not be the safest route when seeking long-term compounding capital appreciation. So, what is an investor to do? One option is to work with a professional advisor who can help design a portfolio suitable to your risk tolerance and objective.

However, if you want to manage your own assets, consider designing a consistent sell strategy, or as we like to call it, a sell discipline.

UNDERSTANDING VOLATILITY

It's 2022. The market is concerned with record-high inflation, rising rates, midterm elections, supply chain constraints, and geopolitical warfare. The stock market has no interest in who wins an election; instead, the market is concerned with uncertainty, which is omnipresent at the moment.

And staged in front of a crowd of investors, gleaming in the uncertainty spotlight is inflation—the rising cost of goods and services globally. From 2020-2021, Capital Hill injected loads of cash directly into consumers' pockets. That cash was spent on goods and services.

Demand heats up as more cash enters the marketplace and the economy expands. As demand rises, so do prices, seeking an equilibrium where the cost of goods sold aligns with demand.

Those rising prices are called inflation. Some inflation is a healthy facet of an efficient market, but too much can be dangerous to consumers. Thus, the Federal Reserve has to step in by raising interest rates—essentially making access to cash more challenging—to slow economic expansion.

That's all to say that investors are nervous. The market is uncertain. Volatility is high. Cash looks safe.

This is when your sell discipline would take effect. Consider it a behavioral resource for uncertain periods.

Alright, so how do you design a sell discipline?

INVEST IN TWO CATEGORIES

When investing, think of your money in buckets. We look at just two buckets for this example—long-term compounders and tactical investments—though there are a few others (i.e., conservative and cash buckets).

1. The Long-Term Compounders

These are the long-term winners—the companies and the funds you believe can withstand the abovementioned headwinds. You intend to hold these companies in your portfolio for years, if not decades. They are sustainable.

How do you find these long-term performers? They'll tell you. If not working with a professional advisor, look for mutual funds or companies with solid balance sheets and long-term annualized returns.

One mistake investors can make is looking at the year-to-date (YTD) return. In other words, what have you done for me lately?

The issue with purchasing on recent performance is we'll likely tend to react in the same manner upon selling. Instead, looking at the annualized return—the 5-, 10-, and 15-year performance—is critical. That helps us decipher whether it's simply the fund du jour or a reliable investment.

2. Tactical Investments

Many use the term speculative, but I believe "tactical" is more appropriate. A tactical investment is not your long-term performer. It is an opportunity for some investors to put on your oversized suit and pretend you're a late-80s stock broker on Wall Street (channel your inner Gordon Gekko).

Fine, maybe that's a little far. However, when it comes to investing, it's OK to seek shorter-term holdings or tactical positions as a percentage of your overall portfolio. Reflecting on 2020, certain companies flourished in the work-from-home era; however, upon the economic reopening, some of those companies struggled, falling back to fair market values. Some of those companies resembled tactical positions; they posed more volatility but an opportunity for short-term appreciation.

One key note is tactical investments should still have strong underlying fundamentals—positions that an investor can hold for an extended period if needed.

Before seeking short-term investments, ensure that you have most of your portfolio in long-term compounders. The most significant impact on long-term performance is allowing your investments time to grow—emphasize time IN the market, not timING the market.

BE SLOW TO SELL

Long-term compounders with a strong track record, reliable management, and a consistent business plan need time to grow. However, that doesn't necessarily mean to set it and forget it. Keep an eye on the long-term positions, primarily the fundamentals.

Monitor specific, irreversible changes, including executive changes, manager turnover, or poor fundamental business decisions. These are signs that an allocation change may be in order—it may be time to sell.

I'll repeat that for effect: focus on the fundamentals, not the volatility. Hovering your cursor above the 'sell all' button and right-clicking at the first sign of bad news can pose a significant threat to long-term returns.

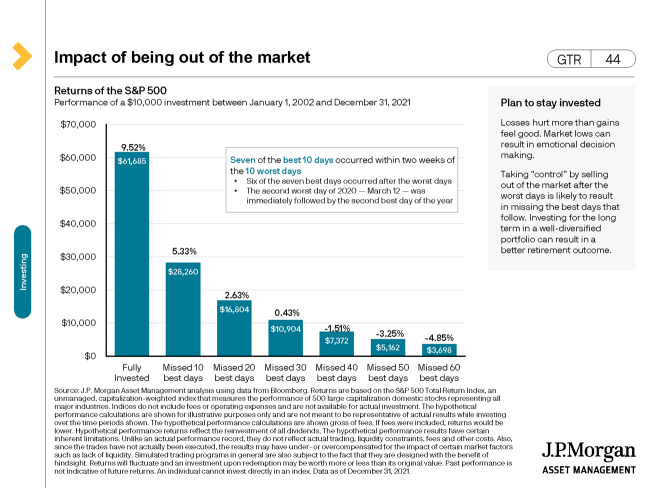

The slide below, extracted from J.P. Morgan's Guide to Retirement [2], illustrates the impact of being out of the market. The chart shows the investment performance of $10,000 invested with the S&P 500 between January 1st, 2002, and December 31st, 2021—20 years or over 5,000 trading days.

Missing the market's ten best days in that period cut the hypothetical investor's return by nearly half. Missing the 30 best days—again, out of more than 5,000—barely left a mark, earning the investor just over $900 in two decades.

Leaving the initial investment untouched resulted in $51,685 of capital appreciation.

The most eye-opening element, however, is the timing of the market's best performances. There wasn't some clear momentous shift leading investors to the pinnacle—it was the opposite.

Seven of the best ten days, from 2002 to 2021, occurred within two weeks of the ten worst days. Six of those days immediately followed the worst days. That means the investors who moved to cash in response to the market's worst days—a natural human reaction—likely missed out on significant long-term returns.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Investing is intimidating, and periods of extreme volatility can be challenging for investors. However, appropriate asset allocation—long-term compounders, tactical positions, fixed-income, etc.—and a well-designed sell discipline can help address our long-term financial objectives.

If you need some help with your portfolio or assets allocations—or if you simply have questions about investing—please call our office at (303) 261-8015 or schedule a free consultation on our website.

Sources:

“Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior, 2020,” DALBAR, Inc. www.dalbar.com [1]

https://am.jpmorgan.com/us/en/asset-management/adv/insights/retirement-insights/principles/ [2]

Disclosures:

Securities offered through LPL Financial, Member FINRA/SIPC. Investment advice offered through Denver Wealth Management, Inc., a registered investment advisor. Denver Wealth Management, Inc. is a separate entity from LPL Financial.

All information is believed to be from reliable sources; however, Denver Wealth Management, Inc. and LPL Financial make no representation to its completeness or accuracy.

The information in the links above are being provided strictly as a courtesy. When you link to any of the web sites provided here, you are leaving this web site. We make no representation as to the completeness or accuracy of the information provided at these web sites. Nor is the company liable for any direct or indirect technical or system issues or any consequences arising out of your access to your use of third-party technologies web sites, information and programs made available through this web site. When you access one of these websites, you are leaving our web site and assume total responsibility and risk for your use of the web sites you are linking to.

The S&P 500 is an unmanaged index which cannot be invested into directly. Past performance is no indication of future results.

Any quoted rate of return is a hypothetical example and is not representative of any specific investment. Your results may vary.

Asset allocation does not ensure a profit or protect against a loss. There is no guarantee that a diversified portfolio will enhance overall returns or outperform a non-diversified portfolio.

Tactical allocation may involve more frequent buying and selling of assets and will tend to generate higher transaction cost. Investors should consider the tax consequences of moving positions more frequently.